Bias and Fairness

Learning Objectives

Define algorithmic bias and recognize that bias is often a subjective property of an algorithm.

Reflect on important case studies demonstrating the real-world impact of bias.

Describe potential bias mitigation strategies and how we can incorporate them into clinical decision making.

What is Bias?

Bias is a term that is often used broadly but has a very precise definition. Bias is always defined with respect to two related concepts: (1) protected attribute(s), and (2) a definition of harm.

- A protected attribute is an attribute about a patient that we want to ensure there is no bias against. Examples of protected attributes include patient age, gender, and ethnicity.

- A definition of harm is how we choose to define when bias is present. Common definitions of harm include an algorithm’s (A) overall error rate; (B) false positive rate (FPR); and (C) false negative rate (FNR).

For a review on metrics such as FPR and FNR, check out this article: Cardinal LJ. Diagnostic testing: A key component of high-value care. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect 6(3). (2016). doi: 10.3402/jchimp.v6.31664. PMID: 27406456

When we choose the protected attribute and a definition of harm, we can then define when an algorithm is biased. Namely, an algorithm is biased if it causes an increase in harm for a subpopulation of patients with respect to the protected attribute(s). For example, if we define the protected attribute as a patient’s race and the definition of harm as the algorithm’s error rate, then the algorithm is biased if its error rate is higher for Black Americans than White Americans.

Which definition of harm should we use - (A) overall error rate; (B) false positive rate; or (C) false negative rate?

It depends! It’s important to recognize that the consequences of false positives and false negatives can be different depending on the task. For example, in colon cancer screening, a false negative (e.g., missing a precancerous polyp on a colonoscopy) is much worse than a false positive (e.g., taking out a potential polyp that turns out not to be precancerous). This means that the consequence of a false negative is much more significant than that of a false positive for colon cancer screening.

Sources of Bias

What causes an algorithm to be potentially biased? Bias can be due to a wide variety of reasons, including population-dependent discrepancies in…

Other than the sources listed below, what are some other potential causes of bias that algorithms might suffer from?

Availability of Data

Especially for machine learning algorithms, it is important for models to be trained on diverse datasets from many different patient populations. If the dataset used to train a model is composed of 90% White patients and only 10% Black patients, then the resulting algorithm will likely perform inaccurately on Black patients.

This is a common problem not just for machine learning algorithms, but also in insights from randomized control trials! For example, take a look at the 2023 ISCHEMIA Trial1 from the American Heart Association. According to Supplementary Table 1, approximately 77% of the patients in the study were male. Would you trust the insights from the trial for your female patients?

1 Hochman JS, Anthopolos R, Reynolds HR, et al. Survival after invasive or conservative management of stable coronary disease. Circulation 147(1): 8-19. (2022). doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONA HA.122.062714. PMID: 36335918

Pathophysiology

Different patient populations may have different underlying mechanisms of disease, and so lumping patients together using a single predictive algorithm may limit that algorithm’s ability to represent all the different mechanisms of disease.

Quality of Data

Suppose we have two CT scanners in the hospital: Scanner 1 and Scanner 2. Scanner 1 was made in 1970 and Scanner 2 was made in 2020; as a result, Scanner 1 produces very low-quality, low-resolution images compared to Scanner 2. If we learn an algorithm to diagnose a disease from CT scans, then the algorithm will likely perform worse on input scans from Scanner 1. This is because lower quality scans contain less information about the patient, and so patients imaged with Scanner 1 will be inherently less predictable.

How Data is Acquired

The data that we choose to collect to learn an algorithm can also introduce biases. For example, suppose you are investigating the relationship between number of leadership positions and match rate for medical students. Focusing only on leadership positions might result in algorithms that are biased against students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds who may have to focus on things such as taking care of loved ones or part-time employment that was not factored into the initial algorithm design. In summary, it is important to be thoughtful about not only algorithms, but also datasets as potential sources of bias!

How might collecting too many data features bias algorithms?

Case Studies

To better understand the sources of algorithmic bias and why they are important, let’s look at some commonly cited case studies (both clinical and non-clinical):

Pulmonary Function Testing (PFT)

PFTs are used in clinical practice to evaluate lung health. The patient’s measured lung values are compared with the expected lung values given the patient’s age, height, sex assigned at birth, and ethnicity among other factors.

Researchers have found that using a patient’s race as input into the expected lung value calculation can result in different PFT results, with implications for access to certain disease treatments and disability benefits. However, they also report that using race has also allowed patients to benefit from treatment options that they would have otherwise not had access to based on societal guidelines.

The 2019 American Thoracic Society (ATS) guidelines currently offer both race-specific and race-neutral algorithms, leaving it up to the discretion of the provider to determine how PFTs are used in clinical practice. Other historical examples of bias in clinical medicine include eGFR calculations, opioid risk mitigation, and care assessment evaluation as functions of race and other patient demographic information. To learn more, check out the Health Equity article from List et al.2

2 List JM, Palevsky P, Tamang S, et al. Eliminating algorithmic racial bias in clinical decision support algorithms: Use cases from the Veterans Health Administration. Health Equity 7(1): 809-16. (2023). doi: 10.1089/heq.2023.0037. PMID: 38076213

COMPAS/ProPublica

In 1998, a private company built the COMPAS algorithm, which is an algorithm that takes in information about arrested/incarcerated individuals and returns a prediction of how likely the individual will commit future crimes. Inputs into the COMPAS algorithm include individual demographics, criminal history, personal and family history, and the nature of the charged crime among others.

The COMPAS algorithm is used in the real world to help the judiciary system set bonds and evaluate arrested individuals. High (low) COMPAS scores mean more (less) likely to commit future crimes.

ProPublica is a nonprofit journalism organization that conducted an independent evaluation of the COMPAS tool in 2016. Their main finding was that COMPAS is biased.

- The distribution of COMPAS risk scores skews low for white individuals but more uniform for black individuals. In other words, white individuals were more often “let off the hook” than black individuals for the same crime.

- Looking at historical data, the false positive rate (FPR) was significantly higher for black individuals than white individuals. In other words, COMPAS was more likely to incorrectly predict that a black individual would commit a future crime.

COMPAS Developer Response to the ProPublica report was that COMPAS is not biased.

- Area under the receiver operating curve (AUROC), a metric of classifier “goodness,” for black and white subpopulations are equal. Therefore, COMPAS is not biased and we can make sure the FPR of both populations are equal by setting different classifier thresholds for the two subpopulations.

Image Generation Using Google Gemini

In late 2023, Google introduced a new generative AI model called Gemini, which is able to complete a variety of tasks such as generating images from input text descriptions. Gemini was released to the public, and users quickly found that Gemini stood out from prior generative models because it was able to generate more diverse sets of images, such as producing images of people of color when prompted for an “American woman” or producing images of women when prompted for historically male-dominated roles, such as a lawyer or an engineer. This was seen as a major step forward in tackling the bias associated with other generative models.3

3 Nicoletti L and Bass D. Humans are biased. Generative AI is even worse. Bloomberg. (2023). Link to article

However, an unintended side effect was that the model also generated historically inaccurate images when prompted for images of “1943 German soldiers” or “US senators from the 1800s.” In these settings, it would be inaccurate to generate images of people of color given these input prompts.

How can we reduce bias?

The most common reason why bias occurs in machine learning is that we train models to be accurate on the “average” patient. In other words, if there are more patients from one subpopulation than another in the dataset used to learn an algorithm, then the algorithm will almost certainly be more accurate on the majority population. Naively learning algorithms in this fashion will result in accurate but biased models.

On the other hand, we could instead implement a completely random algorithm - for example, deciding whether a patient should be admitted or not solely based on the flip of a coin. Such an algorithm would be completely unbiased, but not very accurate.

These two examples demonstrate that in general, there is a tradeoff between accuracy and bias. As we train models to be more accurate, they often become more biased at the same time. Researchers are currently working on ways to overcome these limitations4, but this is an incredibly common empirical finding that we see in practice.

4 Chouldechova A, Roth A. The frontiers of fairness in machine learning. arXiv Preprint. (2018). doi: 10.48550/arXiv.1810.08810

Fairness Doesn’t Stack

Why is training both fair and accurate models hard? There are a lot of complex parts to the answer to this question, but one important reason is that fairness does not stack.

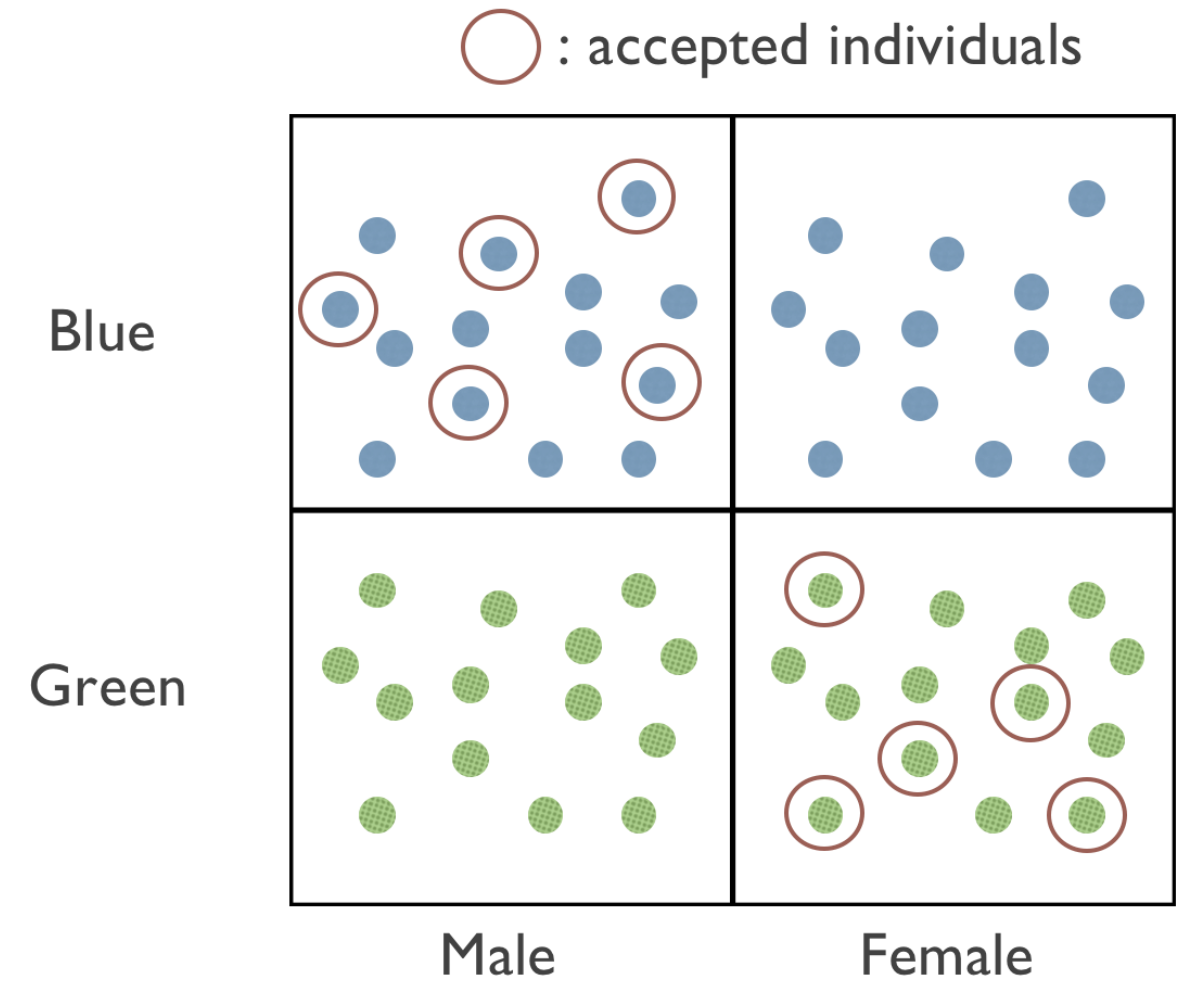

Imagine that we have a screening tool that seeks to predict whether a patient has a disease with 50% prevalence in the population. Using lower sensitivity as our definition of harm, suppose that

- Our screening tool is unbiased with respect to patient gender (i.e., male vs. female).

- Our screening tool is also unbiased with respect to patient race (i.e., “blue” vs. “green”).

Even though algorithm is unbiased against blue people and unbiased against females, it can still be biased against blue female people! Here’s an illustrative diagram of one possibility:

In Figure 1, we can see that our screening tool is “fair” with respect to gender and color by only accepting individuals that are either both blue and male or both green and female. Ensuring that models are fair for certain subgroups doesn’t mean that those models are also fair for members of the intersections of those groups, or other entirely unrelated subgroups. In other words, fairness conditions do not compose. This is why fairness is such a hard problem to tackle!

In fact, the currently state of the fairness in machine learning literature is that experts don’t have a good singular definition of fairness for all applications. Many conditions that we might want to achieve fairness (e.g., fair with respect to gender and race) may be provably impossible to achieve in certain cases!5 This is an active area of research, and it’s important to acknolwedge these challenges when discussing bias and fairness in algorithmic systems.

5 Formal proofs of this statement do exist but are well-outside the scope of this course. If this is an interesting topic to you, we recommend this quick (non-technical) read by Santamicone M. (2021). A slightly more technical blog post that covers more of the details is also available by Zhao H. (2020). at CMU.

What can we do about this as clinicians?

The most important thing to help reduce bias is recognize that all real-world algorithms are biased! How algorithms are biased and to what extent depend on your definition of harm and the patient attribute(s) that you’re focusing on. These definitions inherently differ between persons and scenarios. Recognizing our own biases in the algorithms used by both computers and humans is critical so that we make the best decisions for each individual patient.

Hands-On Tutorial

To better understand how bias can impact algorithms, let’s take a look at a simple example of a binary classifier algorithm that seeks to predict whether a patient (1) requires or (2) does not require supplementary oxygen therapy.

What are pulse oximeters?

Pulse oximeters are small devices that measure the oxygen levels in our blood. Clinicians use them to check for hypoxemia, which is a dangerous drop in our body’s oxygen levels. Most healthy patients have an oxygen level of 95 to 100%.

It’s important to recognize that pulse oximeters only estimate our oxygen levels. The gold standard is to obtain an arterial blood gas (ABG) measurement, which requires sticking a needle in the patient and drawing blood.

Are pulse oximeters biased?

Research has shown that compared to ABG measurements, pulse oximeters can be less accurate for patients with darker skin tones.6 Specifically, they can overestimate oxygen levels for Black patients, leading to systemic delays in giving treatments like supplemental oxygen. This happens because pulse oximeters use light to detect the oxygen in our finger, and skin pigmentation can affect how that light is absorbed and reflected.

6 Sjoding MW, Dickson RP, Iwashyna TJ, et al. Racial bias in pulse oximetry measurement. N Eng J Med 383(25). (2020). doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2029240

Weighing the tradeoffs: In most cases, it’s hard to have a test that is perfectly sensitive and specific. When diagnosing and treating hypoxemia, is it more important to have a high sensitivity, or a high specificity? Why?

7 Fong N, Lipnick MS, Behnke E, et al. Open access dataset and common data model for pulse oximeter performance data. Sci Data 12(570). (2025). doi: 10.1038/s41597-025-04870-8

In a few minutes, we’ll take a look at a dataset of real patients from a research team at UCSF.7 The dataset consists of 108 unique patients, 100 of which are hypoxemic. There’s a relatively even split in terms of self-reported race: 59 identify as White and 49 identify as Black.

How to measure bias

We’ll primarily look at 3 different metrics:

- Sensitivity: If the patient does actually have low blood oxygen, did we actually find it with the pulse oximeter? A high sensitivity means we catch all the true cases of hypoxemia.

- Specificity: If the patient does not have low blood oxygen, did we correctly identify them as healthy? A high specificity means we don’t unnecessarily raise false alarms.

- Accuracy: Overall, how good is the pulse oximeter in giving us the right answer?

Start treating patients!

As a doctor, your goal is to identify which patients have true hypoxemia and which do not. If a patient has a pulse oximetry reading less than a certain cutoff, then you will start them on supplemental oxygen. In the Threshold Strategy section below, use your clinical skills to adjust this threshold of when to start oxygen therapy. You will choose between 2 strategies:

- Race Unaware: use the same threshold for all patients regardless of race.

- Race Aware: use different thresholds for patients depending on their race.

Each dot is a patient — blue dots correspond to patients you have accurately diagnosed, and gray dots correspond to incorrect diagnoses.

Threshold StrategyWhite patients

Black patients

Another way to think about the supplemental oxygen problem is how equity and equality differ from one another. What do these two terms mean to you?

Discussion Questions

- Who do you agree with: ProPublica or the COMPAS developers? In other words, do you believe that the COMPAS algorithm is biased based on the evidence presented? Would you be comfortable having it used to determine the outcomes of the judicial system for close friends or family?

- In the hands-on tutorial, we explored how even simple binary classifiers can be biased in scenarios such as determining supplemental oxygen requirements. What other analogous “binary classifier” clinical situations have you encountered? How did you decide your strategy on how to set your own “threshold” for positive and negative labels? Did your strategy vary between different patients?

Summary

Bias is defined based on (1) protected attribute(s) and (2) a definition of harm. Because our definition of harm can vary from person-to-person, bias is often subjective. The impact of bias depends on the clinical scenario and the real-world implications of the definition of harm. It is important to recognize our own internal sources of bias in addition to the biases of clinical and computational algorithms.

Additional Readings

- Nicoletti L and Bass D. Humans are biased. Generative AI is even worse. Bloomberg. (2023). Link to article

- Kearns M, Roth A. Responsible AI in the wild: Lessons learned at AWS. Amazon Science Blog. (2023). Link to article

- Evaluating Model Fairness. Arize Blog. (2023). Accessed 19 May 2024. Link to article

- List JM, Palevsky P, Tamang S, et al. Eliminating algorithmic racial bias in clinical decision support algorithms: Use cases from the Veterans Health Administration. Health Equity 7(1): 809-16. (2023). doi: 10.1089/heq.2023.0037. PMID: 38076213

- Mittermaier M, Raza MM, Kvedar JC. Bias in AI-based models for medical applications: Challenges and mitigation strategies. npj Digit Med 6(113). (2023). doi: 10.1038/s41746-023-00858-z. PMID: 37311802

Made with ❤ by the EAMC Team ©2025.